VINEMONT, Ala. – Stroke is the fifth most common cause of death in the United States, and one Cullman County veteran who survived an incident with circumstances being called miraculous is spreading the word to help others know how to recognize and respond to the condition.

Hanceville native Gerald “Gerry” Sandlin moved to Kansas before joining the Army to serve as a helicopter crewman with the 189th Assault Helicopter Company, 52nd Combat Aviation Battalion in Vietnam. Ultimately, he and his wife Barbara ended up in a quiet country home in rural Cullman County near Vinemont.

As a soldier, he faced mortal danger in the air many times. The last time it happened, though, there were no bullets flying. It was a stroke that almost grounded Sandlin for good, and a unique set of circumstances–that, to many observers, were too coincidental to be a coincidence–that saved his life.

First, what is a stroke?

According to StrokeAwareness.com, a stroke is an attack in which arteries in the brain burst or become blocked. The resulting lack of oxygen can kill brain cells, leading to impairment of speech, sight and mobility, and even death.

The condition can occur at any age: 20% of people who have a stroke are younger than 55, and the chance of stroke increases with age. African-Americans, Hispanics and Asian/Pacific Islanders have a higher risk of stroke than people of other races. Women are more likely to have a stroke than men, and more women die from stroke than from breast cancer every year. You are at greater risk if a family member has had a stroke.

Crisis in the air

On Feb. 13, 2018, Sandlin and his wife were on a Delta Airlines flight from Salt Lake City, Utah to Atlanta, on their way home from visiting family in Oregon. They were supposed to have flown in the day before, but their Feb. 12 flight was canceled for an unknown reason. That would become an important coincidence.

Somewhere over the Midwest, according to Sandlin, “I decided to have a stroke.”

He began to feel odd and his vision was blurring. He turned to his wife, who had her own previous encounter with a stroke, and she saw the signs.

Barbara Sandlin stood up and announced, “I need help, and I need it now!”

Gerry Sandlin was suffering a particular form of stroke known as a basilar artery thrombosis, an aggressive arterial blockage that occurs at the top of the brainstem where oxygenated blood is distributed to much of the brain. The mortality rate is 85%, and the few survivors often find themselves in a “locked-in” state of total paralysis. Sandlin’s only chance would be a fast response from people who knew exactly what they were doing.

Remember that coincidence thing?

Gerry Sandlin continued, “There were two doctors on board, no equipment or nothing. But they recognized it was a stroke; they talked to me at length and MedLink told them to get down as soon as possible, and suggested Memphis.”

The one-day delay in their trip put Sandlin on a flight with a cardiologist and urologist, along with an Air Marshal. On top of that, the order to land in Memphis, Tennessee–the closest airport along their route that could take their airliner–put them in a city with one of the best stroke response programs in the country. There, the University of Tennessee Health Science Center operates a mobile stroke unit, a rolling emergency room specifically designed to respond to suspected strokes with equipment like an onboard CT scanner.

Said Gerry Sandlin, “It was lucky that I did go to Memphis. They have what they call a ‘strokemobile.’ It comes right out on the tarmac. The doctor and the paramedic came on board, got me off, threw me in the back of the strokemobile and did a CAT scan, relayed it to the surgeon, and also did a TPA (Tissue Plasminogen Activator, an injected medication designed to dissolve blood clots) right there on the tarmac before we ever left.”

From there, Sandlin was taken to Methodist University Hospital in Memphis, where he spent only one night in intensive care before being transferred to a regular room.

Time is considered to be one of the most crucial factors in response to strokes, as with most medical emergencies. From the identification of the stroke on the flight to the beginning of treatment in the mobile unit, 38 minutes passed; half the time normally required for the beginning of treatment in places without such a unit.

When the physical therapy staff showed up at Sandlin’s hospital room the next day to get him moving with the aid of a walker, the old soldier would have none of it.

He said, “She came in with a walker, and I jumped up and started walking. The hospital has five quadrangles, and I walked around the first quadrangle pulling her. I don’t remember if we went another time or not, but anyway, before that day was over, I had been around all five quadrangles at least twice.”

Sandlin spent the following day at the hospital doing interviews with television and newspaper reporters about his remarkable experience, before being released the day after that.

Today, Sandlin still travels and still flies to visit his children out west, as well as attending Vietnam veterans’ reunions across the country as head of the 189th Assault Helicopter Company veterans’ association. He and his wife have visited the hospital and mobile unit team in Memphis to thank them personally, and have photos of doctors, paramedics and the strokemobile on their living room wall.

Gerry Sandlin reflected, “We were lucky. The kind of stroke I had is supposed to kill you or either lock you in. Your mind runs away, and your body don’t do nothing. But I’m lucky; my mind runs away and doesn’t talk to my body, but I do what I want to.

“You know, there’s minutes that we’d be flying, going in to insert troops or either pull them out. Sometimes it was a hot LZ (landing zone), and I didn’t know if I was going to make it to the LZ or make it home that night.

“This is different. You expect death in a combat zone; you don’t outside. It means the world to me to be living, to tell other people that I’m a fighter. I have overcome several things, and yeah, I’ve got problems, but I think that my spirit inside me keeps fighting and I don’t give up. My body may drag a little bit, but my mind doesn’t.

“And like she said, we plan reunions. I’ve got a Vietnam veterans’ organization that I head up; I’ve got people all over the country, and I’m in contact with them–some almost every day. But it keeps me going. I really appreciate being alive.”

The couple regularly talks to “anybody that’ll listen” to raise awareness of the signs of a stroke, how to respond to one and the need for speed in the process, promoting the BE FAST approach of StrokeAwareness.com.

Recognizing and responding to a stroke

StrokeAwareness.com spokesman Joe Duraes, who arranged The Tribune’s meeting with the Sandlins, shared information about recognizing and responding to strokes.

A SUDDEN ONSET of the following symptoms may indicate stroke. Note that these symptoms or a combination of them are not unique to stroke, but if they are sudden and out of the ordinary, they may indicate a sign of stroke and require immediate attention.

10 signs and symptoms of a stroke

- Confusion

- Difficulty understanding

- Dizziness

- Loss of balance

- Numbness

- Severe headache

- Trouble speaking

- Trouble walking

- Vision changes

- Weakness

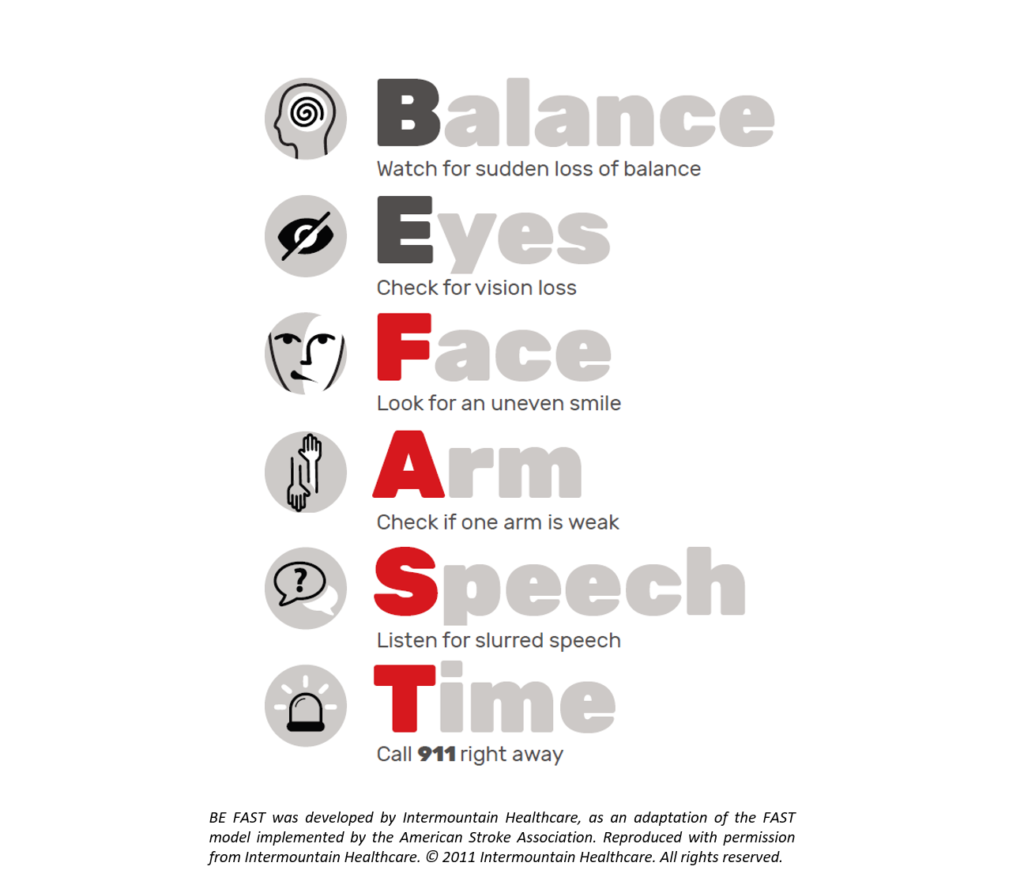

The group’s recommended response to a possible stroke is summed up as BE FAST:

- B = Balance, watch for sudden loss of balance

- E = Eyes, check for vision loss

- F = Face, look for an uneven smile

- A = Arm, check if one arm is weak

- S = Speech, listen for slurred speech

- T = Time, call 911 right away

To learn more about stroke and how to recognize all 10 signs and symptoms, visit www.strokeawareness.com.

Copyright 2019 Humble Roots, LLC. All Rights Reserved.